06 Jan A new way to help the immune system fight back against cancer

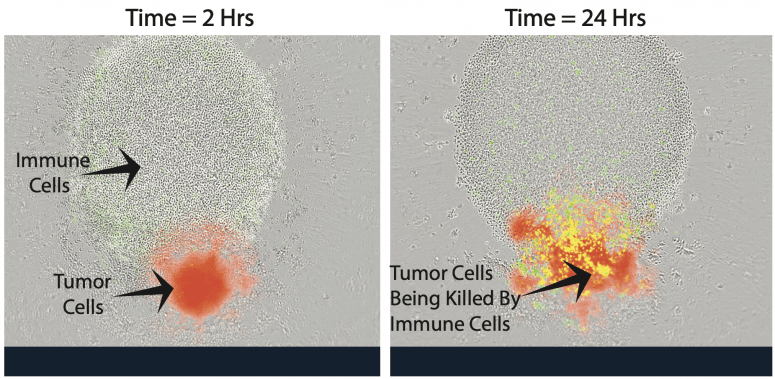

Immune cells, which look like small, clear circles, next to a small red sphere of neuroblastoma (cancer) cells. When researchers add an anti-neuroblastoma antibody, the antibody sticks to the cancer cells. This enables the immune cells to recognize the antibody-coated neuroblastoma cells and kill them. IMAGE COURTESY OF AMY ERBE

Scientists at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health are breaking new ground to make cancer cells more susceptible to attack by the body’s own immune system.

Working in mice, a team led by Jamey Weichert, professor of radiology, and Zachary Morris, professor of human oncology, is combining two different techniques in its approach, using targeted radionuclide therapy, which delivers a low dose of cell-weakening radiation specifically to cancer cells, followed by immunotherapy, which helps the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. The animal research is laying the foundation for future human and veterinary clinical trials.

“This has a huge advantage because we can target tumors systemically, regardless of number and anatomic location,” explains Weichert. “I often describe it as scuffing up the tumor with this low amount of radiation to make it easier for the immune system to recognize it.”

The team has been awarded $12.5 million in funding from the National Cancer Institute to further develop this approach to treating potentially any cancer, including prostate cancer, melanoma, and pediatric neuroblastoma, as well as cancer in dogs.

The research effort includes four projects and four research and support cores led by Weichert, Morris and a suite of other UW–Madison researchers — many of them members of the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center.

In contrast to traditional external beam radiation therapy, which is commonly delivered from an X-ray source outside of the body to one or a few tumor sites, targeted radionuclide therapy involves linking a radioactive atom (also known as a radionuclide) to a molecule injected into the body that is then taken up mostly by cancer cells at all tumor sites..

Weichert’s team uses a radioactive element and a molecule that mimics a kind of lipid found in rapidly dividing cancer cells. They also use imaging techniques to enable precision dosing of the agents, which are injected into the bloodstream.