27 Feb All creatures great and small: Sequencing the blue whale and Etruscan shrew genomes

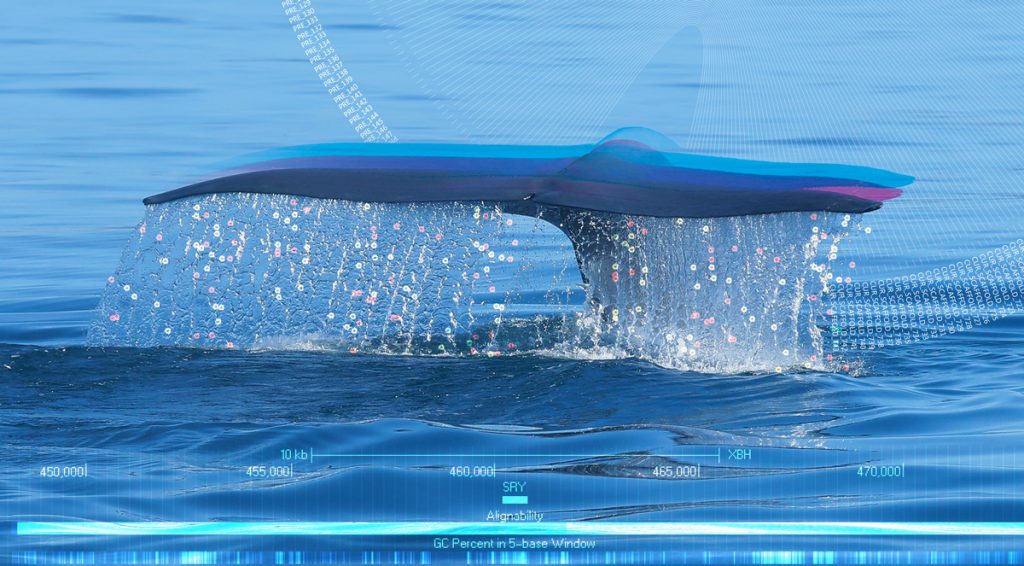

Photo of blue whale tail fin provided by Jeff Jacobsen, with composite overlay incorporating data elements from the blue whale paper rendered by Huston Design.

Size does matter when it comes to genome sequencing in the animal kingdom, as a team of researchers at the Morgridge Institute recently illustrated when assembling the sequences for two new reference genomes — one from the world’s largest mammal and one from one of the smallest.

The Blue whale genome was published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution and the Etruscan shrew genome was published in the journal Scientific Data.

Research models using animal cell cultures can help navigate big biological questions, but these tools are only useful when following the right map.

“The genome is a blueprint of an organism,” says Yury Bukhman, a computational biologist in the Ron Stewart Computational Group at Morgridge and first author of the published research. “In order to manipulate cell cultures or measure things like gene expression, you need to know the genome of the species — it makes more research possible.”

The Morgridge team’s interest in the blue whale and the Etruscan shrew began with James Thomson, emeritus director of regenerative biology at Morgridge, and his research on the biological mechanisms behind the “developmental clock.” It’s generally understood that larger organisms take longer to develop from a fertilized egg to a full-grown adult than smaller creatures, but the reason why remains unknown.

“It’s important just for fundamental biological knowledge from that perspective. How do you build such a large animal? How can it function?” says Bukhman.