26 Jan These tomatoes are out of this world… or they will be soon

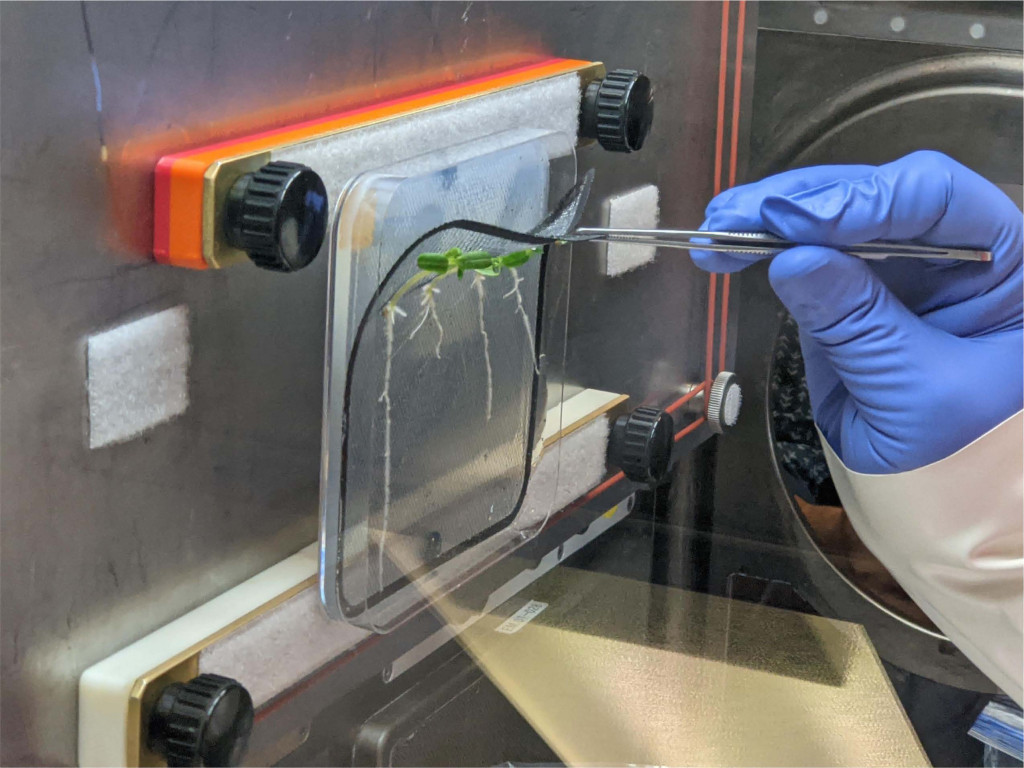

Plants are harvested in the Life Science Glove Box. Photo courtesy of the Gilroy Lab

Simon Gilroy and his lab are no strangers to sending plants into space. And, at the end of January, the University of Wisconsin–Madison botany professor and his team will be doing it again for their sixth experiment with NASA on the International Space Station, this time with tomatoes.

Nicknamed TASTIE, which is short for Trichoderma Associated Space Tomato Inoculation Experiment, the researchers hope to better understand how plants grow without gravity and whether there are ways to help plants cope with the stressors involved with growing in space flight.

“Plants know up from down, right? They don’t have a brain or anything like that, but shoots grow upwards, and roots grow downwards. They clearly are using directional information,” Gilroy explains.

But remove gravity from the equation and things get wonky. And stressful. That’s where the team is hoping a common fungus they’re sending up along with the tomatoes will come in.

The fungus is a type from the genus Trichoderma, which is prevalent in all kinds of soils. On Earth, the fungus is known to be beneficial for plant growth, making the plants they grow with hardier for later encounters with threats and stressors.

Gilroy explains that on Earth, when a plant’s roots come into contact with the fungus, it sets off all kinds of alarms in the plant. Believing itself to be under attack, the plant switches on a series of genes that effectively activate its defense systems. Even after the plant realizes the fungus is not a threat and the two organisms establish a mutually beneficial relationship, the plant’s defensive genes stay on.